A Few Words on the Title Page and Second Preface

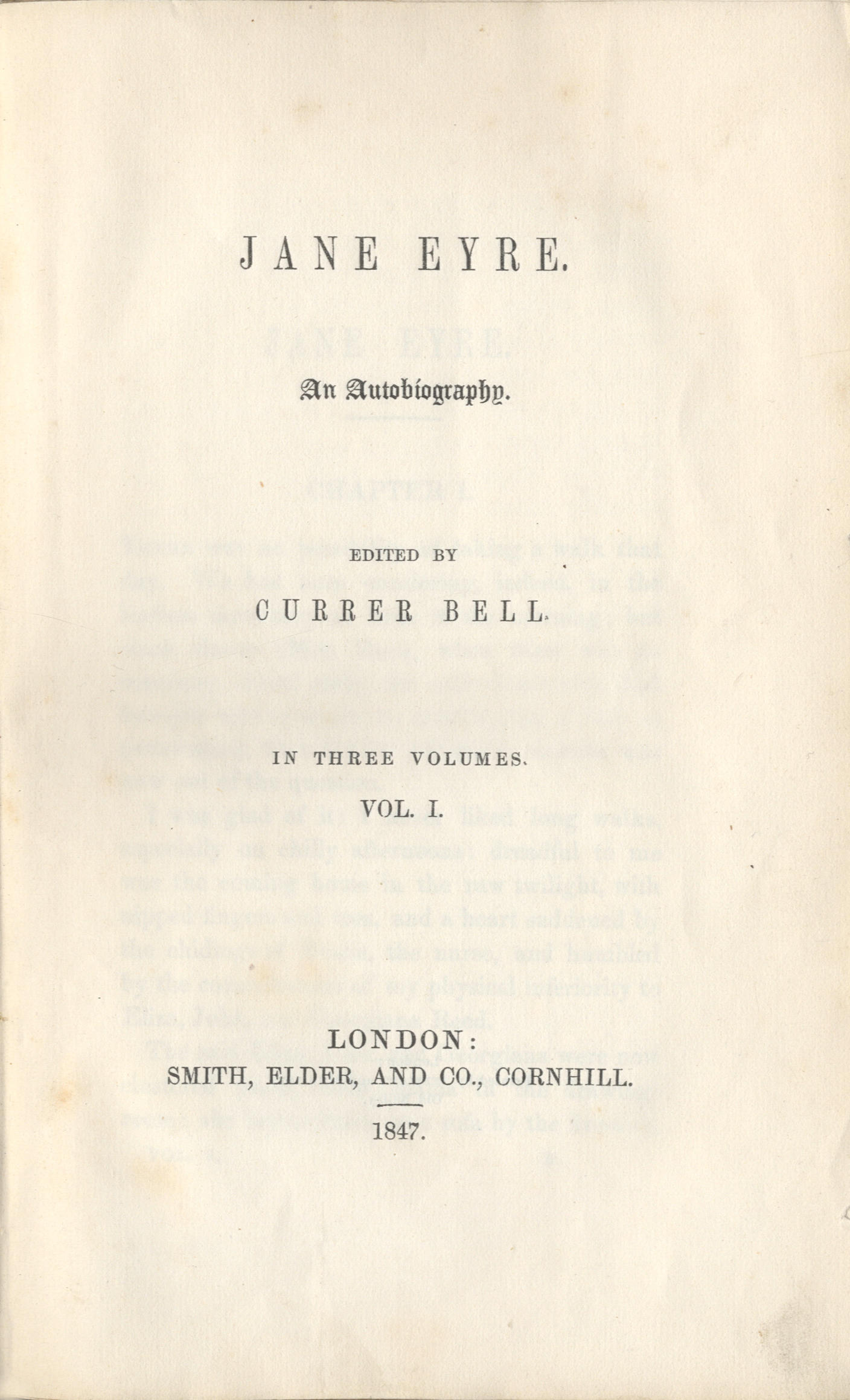

The title page of a book says a lot, even if it says very little. Here is a facsimile of the first edition title page of Jane Eyre:

As you can see, Jane Eyre is posing as an autobiography, and Currier Bell, Charlotte's pen name, is only "editor." Also included, of course, is the publisher's information, and the year of publication: 1847.

I couldn't help but compare this title page to that of Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe (I studied Moll last spring and she hasn't yet vacated my brain). The two couldn't look more different. Look here:

The most obvious difference between these two title pages is that Moll's has quite a bit going on. A lot of explanation--there is a summary of the woman's life, with a focus on how licentious her life is (but of course it's all good because she dies a penitent).

However, there are some similarities going on here: neither of the authors' names are the focal point--Currier Bell is a pen name, and its font size is minor compared to Jane's; Defoe's name does not appear at all. Both title pages establish that these works (of fiction) are pieces of memoir or autobiography; so, "true" stories.

The prefaces to these works also relate to one another. Defoe writes a long preface establishing why it's okay to read a work full of horrible, horrible sin, as it can be used as an example of how not to live. He addresses his audience quite well, as he knows many readers will be religious (and hypocritical; he knows they will eat up all the dirty stuff, and he does a good job of justifying why it's okay for them to dig in).

Charlotte doesn't address her audience in the first edition of Jane Eyre--"A preface to the first edition of 'Jane Eyre' being unnecessary, I gave none"--but she does say a word or two when the second edition is released--"[T]his second edition demands a few words both of acknowledgment and miscellaneous remarks."

To give the history of a wicked life repented of, necessarily requires that the wicked part should be make as wicked as the real history of it will bear, to illustrate and give a beauty to the penitent part, which is certainly the best and brightest, if related with equal spirit and life.

Having thus acknowledged what I owe those who have aided and approved me, I turn to another class; a small one, so far as I know, but not, therefore, to be overlooked. I mean the timorous or carping few who doubt the tendency of such books as 'Jane Eyre': in whose eyes whatever is unusual is wrong. [...]

Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion.Charlotte finds it necessary to let her pious audience know that there is a difference between what society finds "normal" and what is morally just. "Men too often confound them: they should not be confounded: appearance should not be mistaken for truth; narrow human doctrines, that only tend to to elate and magnify a few, should not be substituted for the world-redeeming creed of Christ." Charlotte is definitely Christian, and sadly, she must justify this to her audience. The upside is that she does this quite beautifully, while also maintaining that morality is more complex than black vs. white. Just because a book includes sinful action does not mean the book itself is satanic. Charlotte also craftily establishes her duty as a writer:

The world may not like to see these ideas dissevered, for it has been accustomed to blend them; finding it convenient to make external show pass for sterling worth--to let white-washed walls vouch for clean shrines. It may hate him who dares to scrutinize and expose--to rase the gilding, and show base metal under it--penetrate the sepulchre, and reveal charnel relics: but hate as it will, it is indebted to him.Charlotte realizes that being a writer has worth--it is she who unearths "charnel relics." Even if the dissenters won't admit it, they owe her so much.

In both prefaces, Defoe and Charlotte must address pious readers and prove why their novels are worth reading. Moll Flanders was released in 1722. Over 100 years had passed when Jane Eyre was released, and yet the writer and audience still had to address what is superficial morality and what is complex. Both novels were extremely successful at the time of publication, so each work established a relationship between writer and general public. Perhaps Charlotte was hopeful her audience would be shrewd enough to read the difference between conventionality and morality when she first released Jane Eyre, but she in fact realized her readers needed her to spell out the differences. Comparatively, instead of correcting his audience, Defoe capitalized on his readers' duplicity--he paved a road they could walk on, by saying dirty isn't dirty if you can learn from it. In a twisted way, Defoe is saying the same thing as Charlotte: everything is not as black and white as you choose to see it. He even challenges his readers to take responsibility for how they view the story:

The reader must decide for himself what is true and what isn't. Of course, Defoe actually wrote a novel, while posing as the editor of poor Moll. So, who or what can we trust, really? It is difficult to say. Perhaps Jane's experience will shed some light.

The world is so taken up of late with novels and romances, that it will be hard for a private history to be taken for genuine, where the names and other circumstances of the person are concealed, and on this account we must be content to leave the reader to pass his own opinion upon the ensuing sheet, and take it just as he pleases.

May 25, 2015 @ 4:33 p.m. (CEST)

Jane Eyre: Take One

So, I've been told I'll really like Jane Eyre. A couple of my close friends are big fans, and many of the people I admire on BookTube really dig the tragic love story as well. (I'm assuming it's tragic. I don't actually know what happens, but most allusions to the story are melancholic). I've read all 7 Jane Austen novels (except for a third of Mansfield Park, but that's because it was a hectic semester and I couldn't stand Fanny Price...but after hearing Ron Lit talk about how secretly bad ass Fanny is, I'm tempted to return to it one day) and Jane Eyre is often compared to Austen. I like Austen, by the way. Part of why I want to read Charlotte Brontë's masterpiece is to see how it interacts with Austen, but I also simply want to see what all the fuss is about. I want to understand the references. Plus, relationship politics & ethics are wildly interesting to me, so I'm eager to see what Brontë has to offer in that department. Although, I must admit, I'm a bit scared I'll find the story to be too romantic--in a Marianne Dashwood sort of way (read: overboard). There's only one way to find out!

The Norton Critical Edition

which Natalie got for me at a charity shop in Scotland

I'm excited to read this edition especially because of all the great essays and deconstruction that happens after you've finished the novel (the party never stops). I've used Norton Critical Editions in the past for Northanger Abbey and Moll Flanders, among others. The essays are typically well-chosen and organized by theme.

May 22, 2015 @ 7:04 p.m. (CEST)

No comments:

Post a Comment